Arabkir: Journeys to Sudan

Among my grandfather’s belongings brought with him from Sudan, was an Armenian book titled Պատմութիւն Հայոց Արաբկիրի (History of Armenian Arabkir), published in 1969 by Antranik Poladian. Inside the front cover, a message accompanied this gift to my grandfather. Translated into English, it reads:

“With friendly and warm feelings, I present this book to Mr. Berge Khatchikian – he who in his heart keeps alive love of the Armenian language and literature”

I believe K. Yegavian was Karnig Yegavian, an Arabkir native who escaped the Genocide and found refuge in Sudan, as referenced in a previous blog. This large volume chronicles Arabkir’s traditions, landscapes, music, and craftsmanship. Notably, it includes a section on Arabkir Armenians who, exiled from their homeland due to massacres and Genocide, established themselves across the world—including Sudan.

This section of the book is attributed to Bishop Derenik Poladian, a Bishop from the Armenian Church in Addis Ababa who visited Sudan in 1960 and wrote of the Arabkir Armenians in Sudan. We will summarize that chapter, shedding more light on the journey from Arabkir to Sudan.

Having seen the photos of life in Arabkir and of Armenian life in Sudan, it has become easier to try and imagine what life was like for these early migrants. So far from their home of Arabkir, they set up shops, mills and commerce on the banks of the Nile in an unfamiliar environment, both geographically and culturally. They were sometimes the only non indigenous people in the area, having to learn new languages and use their rich tradition of crafts, trade, agriculture and their mercantile networks with other Armenians in the Middle East to thrive in Sudan.

Bishop Derenik Poladian on Sudan’s Armenians:

By the late 19th century, Armenians, particularly from Arabkir and Akn, began settling permanently in Sudan. The Hamidian Massacres of 1894-1897 and the Adana Massacres of 1909 triggered further waves of migration, bringing Armenians to Egypt and Sudan. Sudan’s reputation as a ‘hospitable shore’ provided safety and opportunity for these displaced communities. Armenians helped each other to escape the problems of their homeland and establish businesses in Sudan, and were in most cases linked closely with larger community and trade structures in Egypt. The following individuals were all natives of Arabkir:

Sarkis Melikian - First recorded Armenian to settle in Sudan, who arrived in the 1840s who, along with his friend Bedros. They established a thriving trading business linking Sudan and Egypt. They accumulated great wealth and extensive estates eventually passing away in the Bahr el Abiad region.

Sarkis Hakobian - Arrived around 1860 as a merchant but fled Sudan when the Mahdist conflict took place resettling in Aswan, Egypt.

The Kurkjian Brothers – Haroutiun, Ghukas, Nazareth, Sedrak, Hovhannes, and Matteos Kurkjian - the most successful of the Sudanese Armenians of their era. Ghukas arrived in Omdurman in 1898 and then brought his four brothers. Haroutioun had died in 1896 in the Hamidian Massacres. They established the Kurkjian Brothers Company in Omdurman, and it became the main supplier of food for the Sudanese government before expanding further intro agriculture and its trade into Europe. Their business also operated as a infrastructure and ports company, making roads, bridges and railway lines. In 1922 the brothers split and established their own businesses. Nazaret, Setraik and Mateos set up a new business in Khartoum with Nazaret’s son Sarkis as the president. Matteos Kurkjian built Sudan’s first modern oil press and flour mill. Ghukas’ children Telemak and Haigazoun established The Kordofan Trading Company. The Kurkjian brothers and their descendents were amongst the most successful Armenians in Sudan at the time and funded Armenian community institutions including Khartoum’s St Krikor Lusavoritch Church.

Philip & Yeghia Apkarian - The brothers moved to Kotok in 1900 and worked in trade. Philipe moved to Omdurman in 1912, but Yeghia stayed in Kotok until 1941 before moving to Omdurman. Philip had no sons - he moved to Cairo in 1947 where he later established the ‘Apkarian Tarmanadoun’ (Apkarian Hospital) in Cairo. Yeghia’s son, Hovsep, went to Caloustian School in Cairo before returning to work in Sudan. Other Armenians who lived in Kodok were Sarkis Chirkinian, Armenak Keoroghlian and Hagop Khanjian.

Sarkis Tarpinian– Settled in Malakal in 1914 establishing a trading house and a mill. A key trader in Malakal who settled there having spent time in Kodok with his maternal uncles, Philip and Yeghia Apkarian. (Through the sudanahye oral history archive we know Sarkis Tarpinian married Keghetsik, a Genocide orphan at an orphanage in Lebanon. Sarkis sent his family to Cairo during World War 2 while he stayed in Malakal and sent money to his family. Following the war they were refused permission to stay in Egypt). In 1948 he moved from Malakal to Omdurman, he had four children (one of whom is the author’s grandmother).

Philip Kalpakian – Born in 1886 in Arabkir, he came to Sudan in 1901. By 1906 he was established in Gedaref as a major trader and held a significant position in government. He established the first railway in Gedaref in addition to a postal service which sought to replace a previous camel based communication system with cars. He was well respected by the English, the Sudanese and the Armenians. E.A Lewa in 1931 wrote that Philip Kalpakian was the grain commissioner for the British East Arab Army and established roads and traffic between Gedaref and other places. He died in 1938 bequeathing his house to the Gedaref Armenian community. Another part of his wealth went to AGBU in Alexandria and Cairo to provide charity to the poor.

Kevork Igibdashian - Kevork lived in Kassala, near what was then the Ethiopian border. After the First World War approximately 10 Armenian families established themselves there. In 1936 approximately 30 Armenians lived in Kassala and Kevork was their representative with the local government. Due to Kevork’s efforts, the authorities offered the Armenians an area to live in and to develop a school, but due to various factors the Armenians eventually rejected this offer. During World War 2 on July 4 1940 the Italians conquered Kassala and used Kevork’s home as their military barracks. When the British took Kassala, some Armenians moved back but they eventually left, leaving the Igibdashian family as the only Armenians there. Kevork’s home was an open space for all Armenians visiting or passing through Kassala.

Other early journeys to Sudan:

To give us a well rounded picture of what Armenian migration to Sudan was like we will complement the account of Arabkir’s Armenians with other stories from other locations in the Ottoman Empire and via other sources:

Mkrtich Ulikyan - Born in Constantinople (now Istanbul) in 1904. During the Armenian Genocide his Father took him, his two brothers and his sister to an American orphanage in Constantinople. He made them enter over the fence and then left, hoping this would give the children the means to survive. In 1920 the 16 year old Mkrtich and his brother left the other two siblings at the orphanage and moved to Egypt to join their Father who had survived the Genocide by moving to Egypt. Mkrtich became a mechanic in Egypt before moving to Sudan where he heard there was a demand for car specialists. In El Obeid he knew no one but was told there was a wealthy Armenian called Sarkis Agha. Sarkis Agha was happy to meet a young compatriot and agreed to fund Mkrtich’s plan to establish a truck business stating “go and buy what you want with this money, enjoy it, when you do not need that money, then you will repay your debt”. Mkrtich worked across tribal and regional lines in Sudan to grow his business to four trucks. He married Azatuhi Matosian, a daughter of a family from Ankara who had escaped the Genocide. After World War 2 he joined the mass repatriations to Soviet Armenia organised by the Soviet Union. The Ulikyans were very soon exiled to Siberia along with other repatriates before going back to Armenia after 1956. He died in Yerevan in 1997.

Hrout Afarian - ‘Digin’ Hrout is in most photos of all the Armenian school students in the 1960s. In the oral histories for this project everyone remembers her, but no one knows much about her beyond that she was a Genocide survivor. In the Genocide she lost her husband and her four children but found her way to Khartoum to join her cousin, Mkhitar Setikian. She later on helped at the Armenian school and had a room in the school that she stayed in. Some notable community comments on her is that she was the “grandmother figure to every child that walked through those doors [of the school]”, “everyone’s adopted grandma” and the “carer to every Armenian”. She died in Khartoum in 1969.

Ardash Kasparian - A native of Arabkir who moved to Egypt after the Armenian Genocide. Friends suggested he move to Sudan to search for business opportunities. He moved to the village of Kamlin and opened a small grocery store. He married and had three children with Verkin, a women who had a treacherous journey to Sudan from the Armenian Highlands by foot, horseback, train and boat. Ardash eventually moved the family to Omdurman and established a larger shop there.

Contextualising these accounts:

The documented lives here each contains an immense journey where they adapted to new climates and cultures to establish a stable life and support their families. If we were able to speak to these people today for the sudanahye oral history archive, no doubt their stories would be full of pain, difficulty and ‘odarootyoon’ (foreigness in Armenian) before they established a life on Sudan’s ‘hospitable shores’.

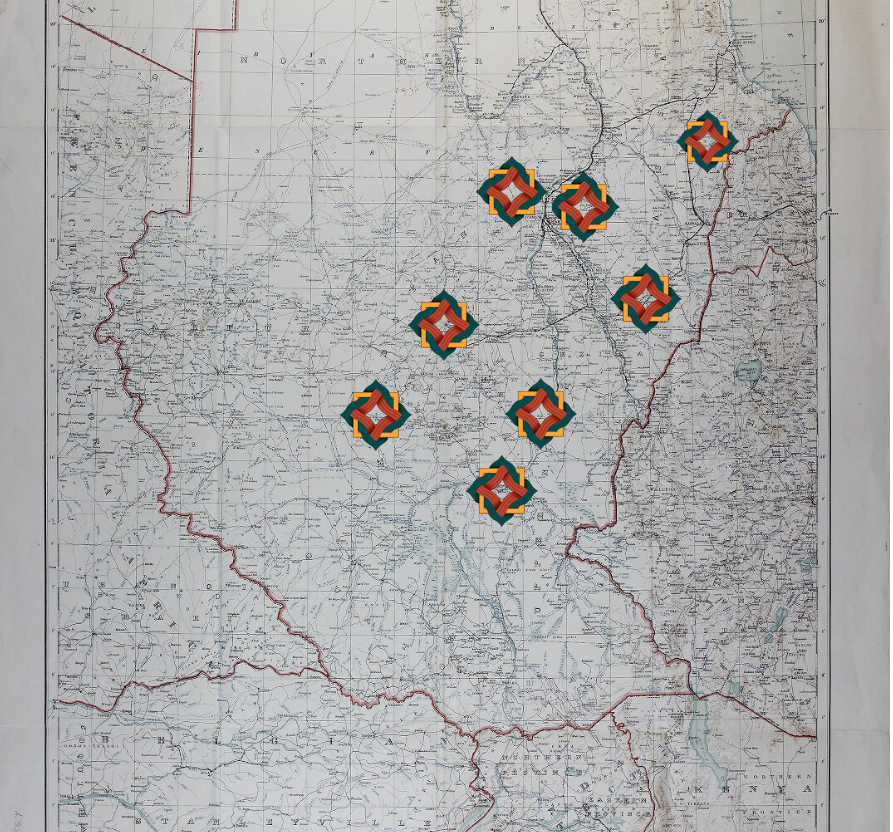

The accounts show that Armenians often originally established themselves in Sudan’s regions in places like Malakal, Kotok, Gedaref, Kamlin, Kordofan, Kassala and more. They also show that Armenian immigration came in waves, the first wave being during the Turco-Egyptian rule ‘the Turkiyya’ in Sudan, from Armenians in Egypt who sought greater economic opportunities. The second wave was those seeking safety and a better life after the Hamidian and Adana Massacres around the turn of the century which also aligns up with the British colonisation of Sudan. And the third wave being those who survived the Genocide (and the exile from Cilicia and Smyrna in 1921-22) often joining family members or friends who have moved to Sudan before.

“With the British in 1898 came a number of Armenians, Syrians and Greeks who settled here. They were traders and money lenders… They owned shops stocked with all manner of goods brought in from Egypt.”

The British hierarchical views of colonial ethnicities encouraged ‘European’ (European meaning non-Sudanese or Arab here) communities to establish trade, and Egyptian communities to work in government, as part of their efforts to reshape Sudan in their imperial vision. In later posts we will explore the early British records which references Armenians in their initial expansion into Sudan.

In Poladian’s account, a pattern emerges whereby Armenians from the regions later moved to the cities of Khartoum or Omdurman. This pattern and its linked history with Khartoum as a colonial city will be explored in a later article.

The account also teaches us the importance of trade networks in encouraging migration to Sudan with fellow exiles from the Armenian highlands, in this case Arabkir natives, giving each other opportunities in their businesses. We saw this in a previous post where Dr Djerjian was employed by the Kurkjian Brothers to manage their business in Sudan and we see it is commonplace in these stories where Genocide survivors joined family in Sudan like Digin Hrout, or where young Armenians were given opportunities by more established elders such as Ulikyan.

The story of the Arabkir Armenians in Sudan is also a reminder that the research on the history of Sudan’s Armenians would be incomplete without touching upon the history of Egypt’s Armenians. All of the Armenians travelled to Sudan via Egypt, with many moving or investing back and forth throughout their lives. Ultimately the stories of Armenian migration above were in the ‘Turkiyya’ and Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Sudan era - both of which linked Sudan to Egypt through a colonial and imperial structure.

In terms of what it tells us about Sudanahye identity, the very fact that this book was being gifted to my Grandfather in Khartoum 64 years after the Genocide began is telling - despite having been born in exile, Armenians of Sudan still felt an attachment to their ancestral homelands. Arabkir’s Armenians leveraged their skills in crafts, agriculture and trade to thrive in Sudan in a time where at first the Egyptian-Turkish rule and later British rule facilitated foreign communities to play a role in the economy.

Notes:

For sources on Bishop Derenik Poladian see his biography and his sermons from Ethiopia here.

To learn more about Arabkir’s Armenians refer to the previous blog post, George Jerjian’s book on Arabkir, the original book by Antranik Poladian and the extensive research done by Houshamadyan.

To find out more about Mkrtich Ulikyan, historin Artsvi Bakchinyan has explored the incredible journey of Mkrtich from Constantinople, to Sudan, to Siberia and finally Armenia here. The popular film Amerikatsi (2022) is also about a Genocide survivor moving to Soviet Armenia as part of the repatriation efforts and being imprisoned.

To learn more about Armenian trade networks and how they operated see Sebouh Aslanian’s From the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean, which examines the commercial activities of New Julfa’s Armenian global mercantile web. While the Sudanese-Armenians were not from New Julfa, the Armenian trade network generally operated similarly.

Extra information on the Kurkjian family and their infastructure business is from Anna Avagyan, Sudanahye Hye Ojakhe in Antranik Dakessian Armenians of Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia (2022)

Sources:

George Jerjian, Arabkir: Homage to an Armenian Community (Bloomington, IN: Xlibris, 2014)

Antranig Poladian, Պատմութիւն Հայոց Արաբկիրի (1969)

The map used can be found in The Sudan Archive of Durham University

Jamal Mahjoub, A Line in the River: Khartoum, City of Memory (2019)

sudanahye oral history archive

Artsvi Bakchinyan - From Sudan to Siberia: Mkrtich Ulikyan’s Odyssey (2020)

Stay updated:

Stay updated on our latest releases - give our social media pages a follow.

We would love to hear from you, whether it be a reflection on this post, a correction or a suggestion, send us an email at vahe@sudanahye.com.